Healthy collaborations?

Recently the supermarket chain Sainsbury’s launched the ‘Heroes’ campaign, offering collectable cards as a give-away alongside specific purchases which were associated (albeit tenuously) with health and wellbeing behaviours: ‘getting active’ ‘teaming up’ ‘being smart’ and ‘doing good’. Although that is hardly clear from the advert:

While we must ask critical questions about the motives behind collaborations between private companies and health or wellbeing initiatives, we must also remember that this sort of sales tactic is hardly new. As Jane Hand has shown, supermarkets and major brands have engaged in health-based promotion and advertising before, making health claims about specific products such as margarine to shift produce. Targeting parents through their children using a health message is also a tried and tested method of promoting a product, idea or behaviour, deployed by both private companies and the government. Perhaps surprisingly, the use of superheroes popular with children to promote health behaviours is also not new. The British Government’s Health Education Council recognised the power of fictional heroes as health promoters, and employed a number of heroes in the 1980s, from Hulk to Superman, collaborating with private companies for the privilege.

On Boxing Day in 1980, an anti-smoking advertisement paid for by the Health Education Council (HEC) and designed by the advertising agency Saatchi and Saatchi, aired on British televisions for the first time. The 30-second clip showed ‘Nick O’Teen’ attempting to encourage a group of children to start smoking, only to be thwarted at the last minute by Superman, who swoops in and throws Nick O’Teen and his cigarettes into the distance.

The TV advert was part of a wider HEC campaign which used the hero Superman in an attempt to persuade children under 11 from ever taking up smoking in their futures.

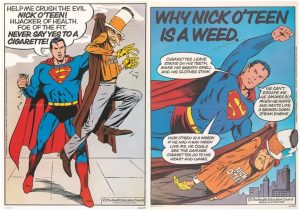

Nick O’Teen Posters. Saatchi and Saatchi for the Health Education Council, 1980a, 1980b, 1980c. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Crown; copyright © Crown, all rights reserved. This information is licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection

Superman’s X-ray vision, he tells viewers, allows him to see inside people’s bodies which is why he ‘Never says yes to a cigarette’. The TV advertisement was part of a campaign run by the HEC from 1980 until 1982, costing in excess of £3.5 million. The campaign deployed a wide range of visual sources, including posters, comic books and badges to encourage children to join Superman in his fight against Nick O’Teen.

This anti-smoking campaign was the product of a collaboration between the Health Education Council and Saatchi and Saatchi, with the heroic image of Superman obviously borrowed (at significant expense) from DC Comics.

Such collaborations between advertisers and the public health education arm of the British government were also not new. The expertise advertisers could offer in the delivery of a persuasive health campaign to the public had been recognised since at least the 1960s, but the Nick O’Teen campaign was still something a little special.

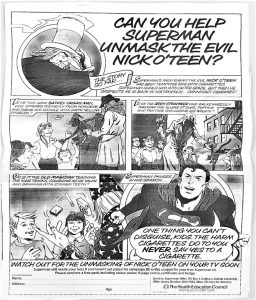

Children are a difficult public to reach with health education. One might assume that they’re a fairly captive audience given they spend much of the week at school, but research indicates that draconian health messages tend to be poorly received and often rebelled against. Outside school children don’t usually have much control over what they consume, so reaching them has to be achieved through media they’re likely to consume, or at school, but in a manner they won’t reject. The Health Education Council opted to place adverts for a free anti-smoking health education Superman Pack in children’s comics (below), sending similar adverts to schools. They also invited children to enter an anti-smoking poster competition.

Superman pack request sheet. Saatchi and Saatchi for the Health Education Council, 1980a, 1980b, 1980c. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Crown; copyright © Crown, all rights reserved. This information is licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection

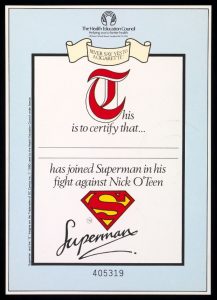

These tactics engaged children directly in the campaign, taking them seriously as an audience with specific tastes, and asking them to contribute (or collaborate). Aside from a chance to enter a competition which might win them a bike, the pack contained a comic book, badges, posters and an anti-smoking pledge children could sign.

Certificate. Saatchi and Saatchi for the Health Education Council, 1980a, 1980b, 1980c. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Crown; copyright © Crown, all rights reserved. This information is licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection

Exciting and enticing though the Superman campaign was, it is very hard to measure if this healthy collaboration between the HEC, Saatchi and Saatchi and DC comics, had the intended effect and reduced the uptake of smoking among Britain’s youth in the late 20th Century. While an estimated 1 in 10 of Britain’s children had requested a Nick O’Teen pack by 1982, the effect this had on smoking is a great deal harder to quantify. Indeed, smoking rates amongst children did not change much over the course of the next 30 years, suggesting that some groups of children were largely impervious to anti-smoking messages, no matter how carefully delivered.

Want to know more? Read the article this short blogpost is based on! The product of another healthy collaboration between Alex Mold and myself as part of the Placing the Public in Public Health project.