The great success story of vaccination in the twentieth century was the eradication of smallpox. Although other public health techniques such as isolation and containment were necessary to eliminate the last few wild cases, vaccination was a key weapon against the disease from the late eighteenth century right up to the disease’s final days.

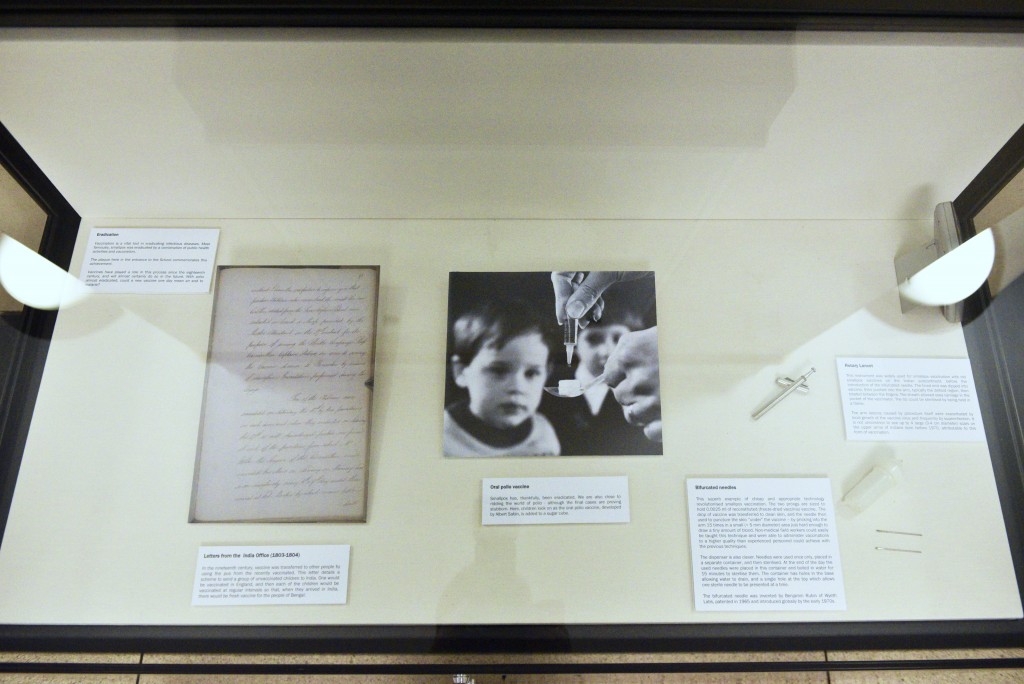

The first cabinet in our vaccination exhibition explores this theme by looking at attempts to eradicate smallpox and poliomyelitis.

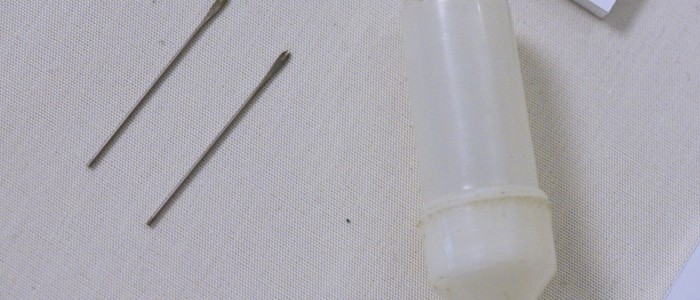

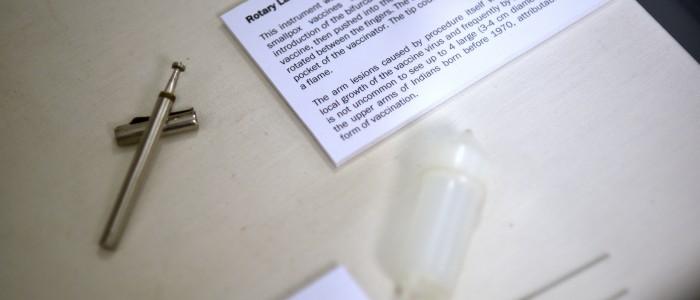

This rotary lancet was loaned to the exhibition by Paul Fine, who worked in Bengal during the 1970s as part of the eradication programme. These were dipped in vaccine solution and then jabbed into the arm of the patient before being twisted. This caused the skin to break, and for the cow pox to get into the wound. While it may seem a little more violent than modern methods, it was a far more efficient and safe procedure than in previous decades, where a surgeon’s lancet would have been used to make a gash in the arm before vaccinia was smeared into it.

This rotary lancet was loaned to the exhibition by Paul Fine, who worked in Bengal during the 1970s as part of the eradication programme. These were dipped in vaccine solution and then jabbed into the arm of the patient before being twisted. This caused the skin to break, and for the cow pox to get into the wound. While it may seem a little more violent than modern methods, it was a far more efficient and safe procedure than in previous decades, where a surgeon’s lancet would have been used to make a gash in the arm before vaccinia was smeared into it.

Apologies to all of you who were reading that paragraph over lunch.

Related to this, Brian Greenwood very kindly loaned us this jet injector. Here, the material is put into a vial and injected under the skin using a high pressure pump. Unlike a hypodermic needle, it can be used multiple times without significant risk of cross-contamination. This is very useful in areas where supplies of clean needles are scarce, or you need to vaccinate a large number of people in one place in a short amount of time.

Related to this, Brian Greenwood very kindly loaned us this jet injector. Here, the material is put into a vial and injected under the skin using a high pressure pump. Unlike a hypodermic needle, it can be used multiple times without significant risk of cross-contamination. This is very useful in areas where supplies of clean needles are scarce, or you need to vaccinate a large number of people in one place in a short amount of time.

This example from the 1970s is about the size of a brief case. So, we gave it its own cabinet. You’ll find it just outside the Manson lecture theatre.

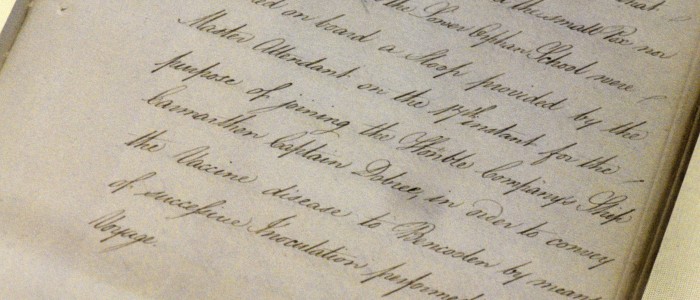

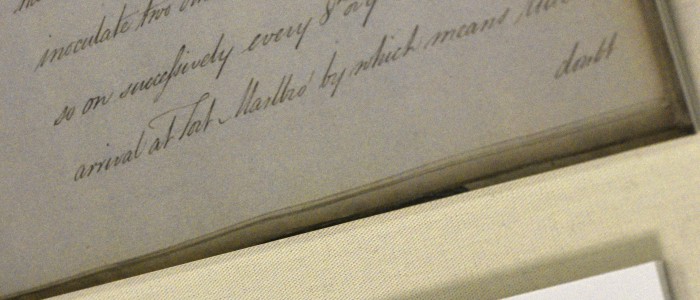

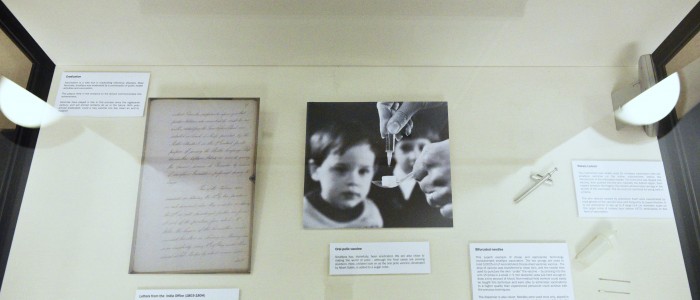

Included with the lancet are some bifurcated needles, also used as part of the vaccination process. These would be dipped into the vaccine and then used to puncture the skin on the arm of the patient multiple times. Vaccine could also be transferred from one person to another. In the late nineteenth century, orphans were used to keep vaccine fresh on long sea voyages. In a letter here from the British India Office, vaccine was taken from the arm of one child and given to another at regular intervals, so that when the ship docked in India doctors could then administer it to British people in the sub continent. Alex Hailey, who kindly gave us permission to reproduce the letter, has written about it here.

We also have an image of a child staring at the Sabin oral polio vaccine as it is administered on a sugar cube. This form of immunisation, which unlike previous versions did not require injection, was used widely across the Western world in the late twentieth century. But the relationship between its inventor, Sabin, and his rival, Jonas Salk, is well worth reading up on if you are unaware. The irony of their career-long battle over their polio vaccines is that we have learnt that both will be required if we are to eliminate the disease completely.

You can read more about our vaccination exhibition here on the website. You can come and visit it in person up until late September 2015. Photography by Anne Korber

Gareth Millward, 24th August 2015