Placing the Public focuses on the human public, and the strand of the project on vaccination is no exception to this. But it is impossible to write a history of immunisation without reference to animals. From the use of cowpox in eighteenth-century experiments on smallpox immunisation to the debates over the efficacy of vaccines against bird ‘flu, our relationship with animals is omnipresent.

When I first began researching vaccination, I knew that there would be some diseases I wouldn’t have space to talk about. But I was surprised at the first decision I would have to make – the decision to exclude agricultural vaccines.

I began looking into the topic by trawling through Hansard, the record of the speeches and written questions in the Houses of Parliament. To my surprise there was about as much discussion of cattle and fowl vaccinations as there was about humans’ problems with poliomyelitis and measles.

Perhaps this shouldn’t have been such a surprise. After all, the wording of the concept of “herd immunity” didn’t come from nowhere. Indeed, the first modern bacteriological vaccines produced by Louis Pasteur were designed to protect cattle from anthrax and chickens from cholera. And one of only two diseases to have been consciously eradicated by human intervention – rinderpest – was not a direct threat to humans. This probably says more about my own ignorance – and, until recently, the relative neglect in the history of medicine – about matters zoological.

Of course, all of this is rather technical; a story of how microorganisms were understood by scientists, and the various processes which saw contagions, animals and humans intersect. One might argue, therefore, that in a history of the British public and public attitudes to infectious disease, animals would be a side story.

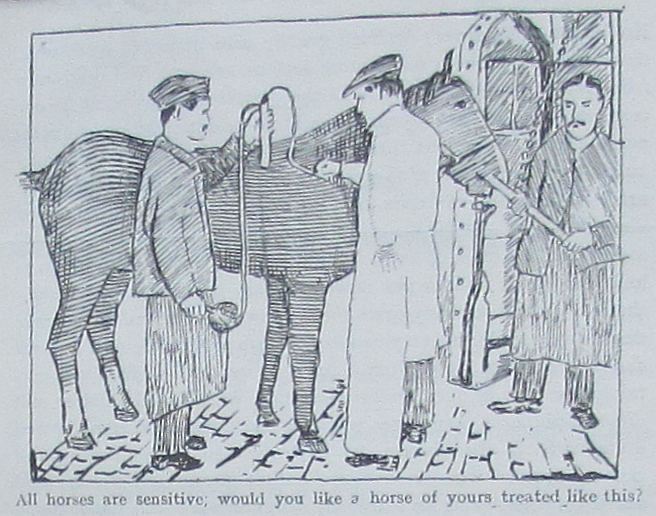

However. One of the driving forces behind antivaccinationism in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was the way in which animals were treated in manufacturing and testing processes. Even as late as the 1940s, there were campaigns against the use of horses in diphtheria immunisation. The anti-toxin could be produced en masse by inoculating horses against diphtheria and allowing immunity to build in the blood. Blood could then be drained from the horses, and the anti-toxin extracted for human use. The horses could be drained multiple times; although this was obviously not a nice existence…[1]

The National Archives: MH 55/1754. Leaflet, National Anti-Vaccination League, ‘A Second Inoculation “try-on” on the People’, attached to letter dated 20 October 1942. The caption reads: “All horses are sensitive, would you like a horse of yours treated like this?”

The British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection ran a large billboard poster campaign during the Second World War against the anti-diphtheria campaign. Aside from statistically dubious arguments about the efficacy of the treatment and its safety, their key objection stemmed from the ‘cruel and misleading experiments on animals’.

The idea of being “contaminated” by animal blood was also a long-running trope of antivaccination thought, as best evinced by the famous Gillray cartoon. Here, people receiving vaccination from an aloof medical man turn into cows.

James Gillray, The Cow-Pock – or – the Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation!, 1802. (Public domain. Original source.)

We see manifestations of this in the 1940s, too. One concerned citizen from North West London pasted a government newspaper advert (encouraging people to vaccinate their children) to a postcard and wrote a strongly-worded condemnation of Minister of Health Ernest Brown’s policies:

![The National Archive: MH 55/1754. Postcard from a woman [name and address pixelated] to the Ministry of Health, received 24 September 1943.](http://placingthepublic.lshtm.ac.uk/files/2017/02/GMHorses3.png)

The National Archives: MH 55/1754. Postcard from a woman [name and address pixelated] to the Ministry of Health, received 24 September 1943.

She added the word “not” to the headline “Diphtheria is Deadly”. Underneath, she writes:

“Immunization must stop. The method of ‘prevention’ is a defiance of nature – Serums are poisoned horse-blood supported by commercial interests.”

Of course, such themes as commercial involvement in vaccination, “unnatural” disease prevention and the idea of poisoning also have a long history in antivaccinationism before and after the 1940s – but here is not the place to discuss them…

Despite the efforts of campaign groups and private citizens, parents continued to present their children for diphtheria immunisation, and by the 1960s the disease was all but eliminated in Britain. The role of animals in this story is, however, often overlooked. Whether it be monkeys and poliomyelitis vaccines, cows and smallpox or horses and diphtheria, the British attitude towards animals has often produced a backlash against certain members of the public against medical treatments.

And these ideas have not fully gone away. There is an on-going debate amongst vegans about the relative morality of using vaccines which are often derived from or tested upon animals. While these cannot be wholly separated from myriad other concerns, it is clear that animals will remain central in the story of vaccination for a good while yet.

Gareth Millward, 28 February 2017.

[1] Mallory Warner, ‘How horses helped cure diphtheria’, The National Museum of American History (15 August 2013) < http://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2013/08/how-horses-helped-cure-diphtheria.html > (accessed 24 February 2017).