Dwight D. Eisenhower. Marc Bolan. Jade Goody. Separated by generation, historical importance and orbits of fame, at first glance they appear to have precious little in common. Nonetheless, all are public figures that have in some way influenced public perceptions of public health.

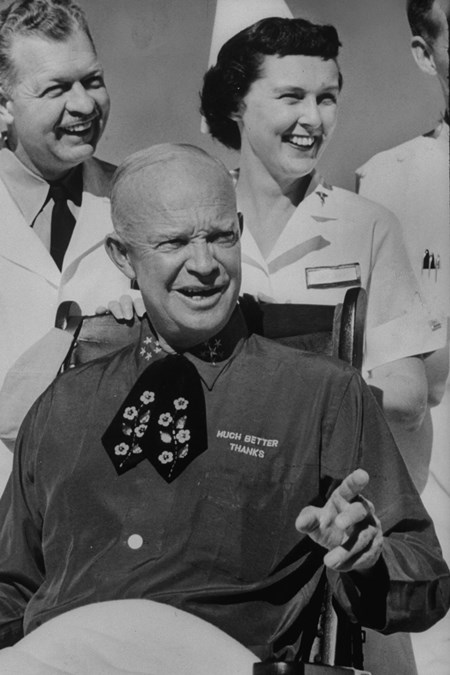

It takes little imagination to think how a President of the United States might impact on public ideas about health. In the most recent US elections, each candidate’s health was a matter of intense public scrutiny following Hilary Clinton’s bout of pneumonia. And the impact of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s polio, contracted at the age of 39, and the establishment of what would become March of Dimes, is well-documented. President “Ike” Eisenhower’s initial heart attack in 1955 and subsequent cardiovascular problems had perhaps wider public rather than private significance, by bringing to national attention the modern epidemic of coronary heart disease among the middle-aged men of Western nations. As Robert Aronowitz makes clear, the publicity generated also served to highlight research being undertaken by epidemiologists in a small town in Massachusetts: the Framingham study.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, at Fitzsimons Army Hospital, after having a heart attack. Source: Carl Iwasaki, Getty

The research in Framingham is hailed as “the first large scale cohort study of chronic disease”. It also ushered in an era of risk factor epidemiology; Framingham “both helped shape and embodied a new approach to individual predisposition to disease that was individualistic, precise, quantitative, and as a result, generally viewed as more scientific than earlier approaches.”[1] The coincidence of the President’s heart condition cannot explain the success or influence of the research, but it did bring coronary heart disease to wider public attention.

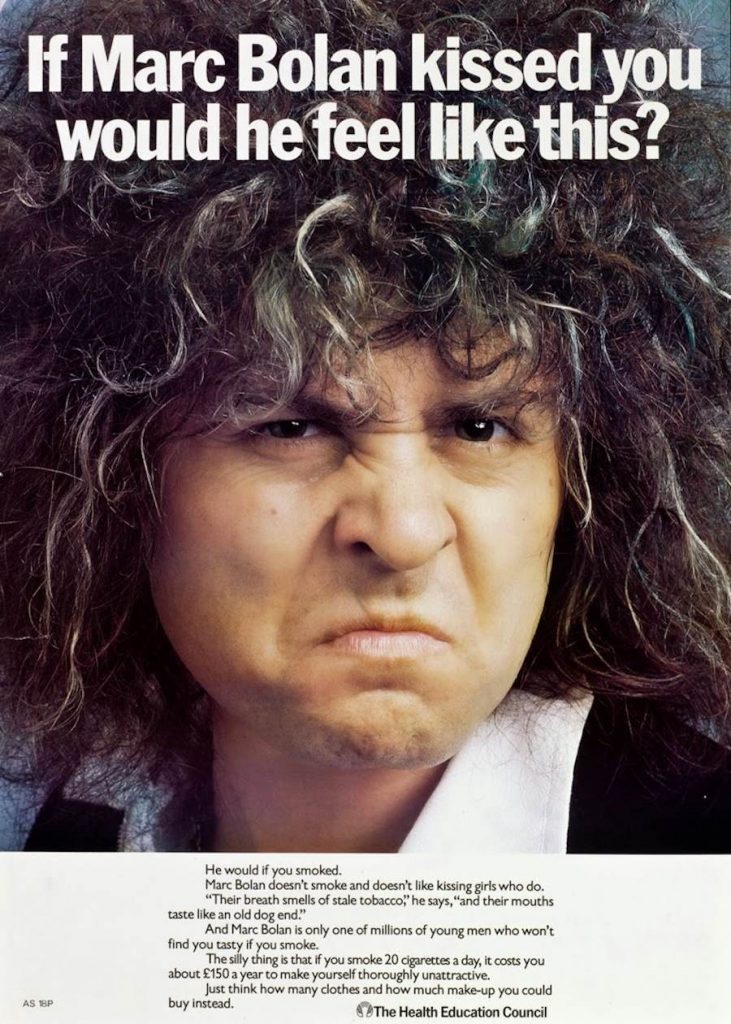

Marc Bolan was of course a very different type of public figure. Before his untimely death in 1977, Bolan was a national heartthrob as lead singer of British glam rockers T-Rex. Bolan may well have been an archetypal pop star of his time – big hair and flared trousers – but he eschewed the cigarette habit of many of his peers. Concurrently, a newer style of public health, initially catalysed by the 1962 Royal College of Physician’s report on the link between smoking and lung cancer, was determined to make tobacco public (health) enemy number one. The Cohen report on health education that followed in 1964 argued that the ‘propaganda’ of tobacco advertising had to be countered in a similar way.[2]

Source: Science Museum Group, Collections Online

Bolan’s use as literal poster-boy of a Health Education Council (HEC) campaign (c.1971-75) chimed with both a public health movement intent on addressing the lifestyle determinants of disease, but also played on the increasing cultural (and consumer) capital of teenagers. The poster informed his young fans that the non-smoking Bolan would withhold his “Hot Love” if they failed to permanently extinguish their smouldering cigarette. In attempting to shift cultural perceptions of smoking as fashionable or sexually attractive, the HEC used nascent celebrity culture to influence potentially impressionable young people’s behaviour in the name of disease prevention. It also worked against that same celebrity culture which tacitly endorsed smoking, drinking and drug-taking by using an icon of the culture to combat such ‘unhealthy’ habits.

By the time that Jade Goody rose to national attention, celebrity culture was in overdrive. Goody claim to fame was initially as a contestant in the third series of the Channel 4 reality TV show Big Brother in 2002. A life in the public eye followed, with an appearance in 2007 on Celebrity Big Brother and numerous mentions in publications of celebrity record such as Heat and OK!. In mid 2008 however, Goody was diagnosed with cervical cancer, which tragically turned out to be terminal. Similarly to Eisenhower’s illness, Goody’s own condition brought cervical cancer to national prominence. More than that however, it also prompted many young women to pursue preventive public health measures. In 2012 the NHS Cancer Screening Programme reported that:

“About half a million extra cervical screening attendances occurred in England between mid-2008 and mid-2009 … The pattern of increased attendance mirrored the pattern of media coverage of Jade Goody’s diagnosis and death. It is likely that the increased screening resulted in a number of lives saved.”[3]

All three individuals illustrate different ways in which public figures have influence public perceptions of public health issues. Straightforwardly, their status as influential public role models can be used to endorse public health initiatives or behaviour change. Their private illnesses have also highlighted research or disease trends previously occluded from public view. And the so-called ‘Jade Goody Effect’ suggests that they may even have saved lives.

Peder Clark, 30 November 2016.

[1] Robert Aronowitz (2015) Risky Medicine: Our Quest to Cure Fear and Uncertainty p.91

[2] Virginia Berridge (2007) “Smoking and the sea change in public health, 1945-2007 History and Policy http://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/smoking-and-the-sea-change-in-public-health-1945-2007

[3] Lancucki, L., Sasieni, P., Patnick, J., Day, T., & Vessey, M. (2012). The impact of Jade Goody’s diagnosis and death on the NHS Cervical Screening Programme. Journal of Medical Screening, 19(2), 89–93. http://doi.org/10.1258/jms.2012.012028